Born: February 1, 1902

Died: May 22, 1967

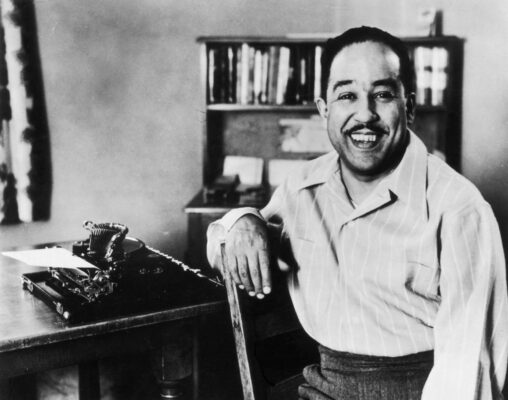

Langston Hughes was more than a poet, he was a force of culture, creativity, and courage during one of the most transformative periods in American history. Best known for his role as a leading voice of the Harlem Renaissance, Hughes used his pen to celebrate Black life, challenge injustice, and craft enduring works that continue to echo across generations.

Family & Early Life

James Mercer Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, to Carrie Langston and James Nathaniel Hughes. His parents separated when he was young, and Hughes spent much of his childhood moving around the Midwest, primarily raised by his grandmother, Mary Patterson Langston, a fierce and resilient woman whose stories of Black pride and perseverance would deeply influence his later writing.

After his grandmother’s death, Hughes reunited with his mother and eventually settled in Cleveland, Ohio, where he attended high school. It was here that he began writing poetry, finding solace in language and rhythm while navigating the challenges of racial identity and economic hardship.

Education and Worldly Experiences

Hughes briefly attended Columbia University in New York City in 1921 but left after a year, feeling unwelcome in the predominantly white academic environment. Yet New York, particularly Harlem, would remain a central influence in his life and career.

He worked a variety of jobs and traveled extensively, including trips to Africa, Europe, and Mexico. These global experiences enriched his worldview and gave him fresh insight into the Black diaspora, fueling his lifelong commitment to social justice and unity through art.

A Literary Powerhouse

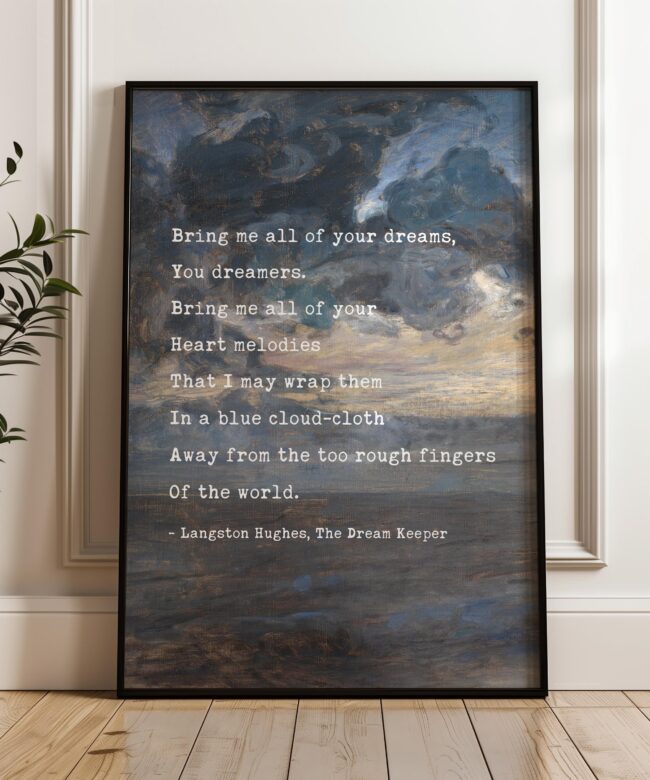

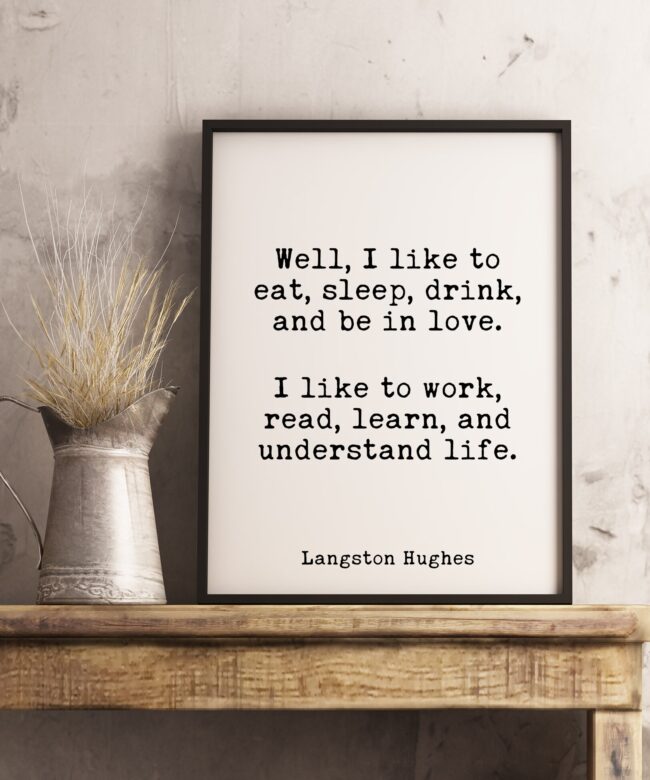

Hughes published his first poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” in 1921, and his first book of poetry, The Weary Blues, in 1926. He followed this with a prolific stream of plays, novels, essays, newspaper columns, and children’s books. His writing was characterized by its clear, accessible language and deep compassion for working-class Black Americans.

Some of his most famous works include:

-

“I, Too” – a short, defiant poem declaring equality and belonging.

-

“Let America Be America Again” – a searing critique of American idealism versus reality.

-

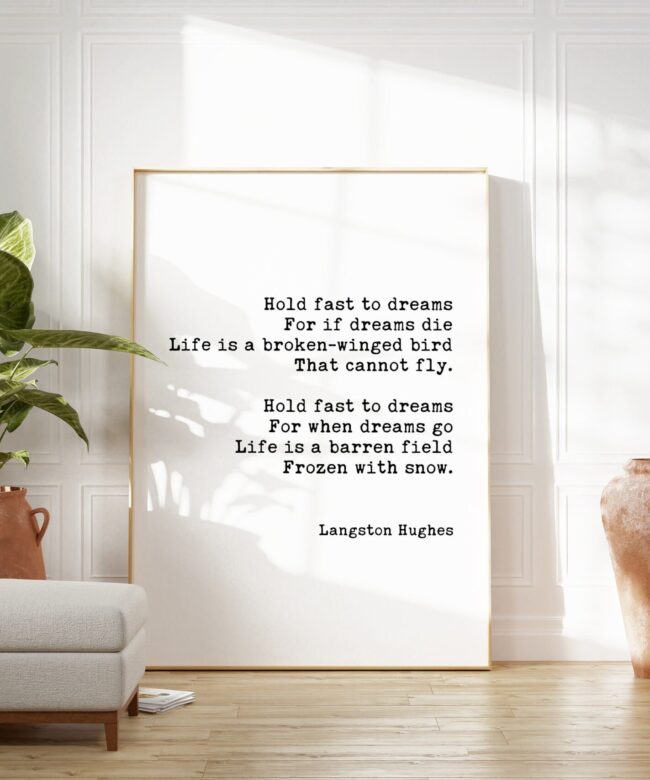

“Montage of a Dream Deferred” – a poetic exploration of Black life in Harlem.

-

“Mother to Son” – a tender and enduring poem about resilience, featuring the iconic line “Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.”

Personal Life & Legacy

Though intensely private about his personal relationships, Hughes never married and left no confirmed record of romantic partnerships. Scholars continue to debate aspects of his identity, including his sexuality, but what remains undisputed is his unwavering dedication to uplifting Black voices and championing civil rights through literature.

Hughes was also known for his creation of the fictional character Jesse B. Semple, or “Simple,” a Harlem everyman whose humorous and insightful musings on race and society became a staple of Hughes’s newspaper column and short fiction.

He died of complications from prostate cancer in 1967 at the age of 65, but his ashes were interred beneath the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem—a fitting resting place for a man who made Harlem sing.

Langston Hughes in Modern Pop Culture

Hughes’s work remains deeply embedded in American culture:

-

His poem “Harlem (A Dream Deferred)” inspired the title and themes of Lorraine Hansberry’s play “A Raisin in the Sun.”

-

Lines from his poems are regularly quoted in films, television, political speeches, and music—including by artists like Beyoncé, Common, and Kendrick Lamar.

-

Hughes was honored with a Google Doodle on February 1, 2015, celebrating his legacy and contributions to literature.

-

His poetry continues to be taught in classrooms around the world, and his voice echoes across social media during Black History Month and times of civil unrest.

Final Thoughts

Langston Hughes was not merely a poet—he was a chronicler of hope, a mirror of struggle, and a dreamer whose words continue to inspire. Through jazz-infused verses and razor-sharp prose, he captured the rhythms of Harlem, the pain of oppression, and the enduring possibility of change. His legacy reminds us that art has the power to speak truth—and that sometimes, the most revolutionary act is simply telling your story.